The Department of Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine is pleased to announce that Harrison Gabel, PhD, is promoted to Associate Professor with tenure. Gabel studies the epigenetic regulation of neurons during development, both in health and in intellectual and developmental disorders. In addition to leading a thriving lab of researchers and students, Gabel is the co-Director for the Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience Graduate Course, oversees the Department’s Works-In-Progress seminar series and has mentored five graduate students who have gone on to advance their careers through postdoctoral research or positions in industry.

“Dr. Gabel’s exceptional research program and dedication to mentoring and education has been a tremendous asset to the Department,” said Linda Richards, PhD, Edison Professor and Chair of the Department of Neuroscience.

“Harrison brings expertise and dedication to the study of epigenetics related to neuronal development and disease,” said Paul Taghert, PhD, Professor of Neuroscience and former interim Chair of the Department. The study of the epigenome is a frontier area of science requiring the development of new techniques and methodologies to study how the genome is regulated by specific proteins and enzymes. The work has important implications for understanding disease mechanisms. “Importantly, his approach is highly collaborative and he is actively pursuing research with Department colleagues that seek to use such molecular information to address new questions about cortical circuit organization and function.”

Gabel joined the Neuroscience faculty in 2015 after receiving his PhD in Genetics from Harvard University in the laboratory of Gary Ruvkun, identifying key components of RNAi machinery in C. elegans. As a postdoc in Michael Greenberg’s lab at Harvard Medical School, Gabel turned to studying methyl binding protein MeCP2, whose dysfunction causes Rett Syndrome. Among other insights into MeCP2’s activity and regulation, Gabel discovered that it homes in on a brain-specific form of methylated DNA—that is, methylation at non-CpG sites—and thereby regulates the expression of very long genes. These genes are highly expressed in neurons and direct distinct aspects of neuronal development and connectivity, and his findings suggest that deregulation of long genes might represent a common underlying cause of neurological conditions including autism spectrum disorders.

As an independent investigator, Gabel has identified that alterations to MeCP2 levels disrupt enhancer function, providing a novel mechanism for gene misregulation underlying Rett syndrome and MeCP2-duplication syndrome. The Gabel lab has also expanded to study numerous other genes and disorders, including DNMT3A, which causes Tatton Brown Rahman Syndrome (TBRS), CHD7, which underlies CHARGE syndrome, NSD1, which causes Sotos syndrome, and PIK3CA, whose mutations lead to a variety of overgrowth disorders.

A model collaborator

Gabel has formed fruitful collaborations with colleagues at WashU, lending his expertise to others’ investigations and pulling in complementary skills to strengthen projects he leads. For example, Gabel and Joe Dougherty, PhD, Professor of Genetics at the School of Medicine, have had a long-running partnership that benefits from Gabel’s epigenetics know-how and Dougherty’s mouse behavior expertise. Recently, Dougherty’s team was leading the development of a mouse model of a newly discovered neurodevelopmental syndrome caused by mutations in MYT1L. “Harrison was instrumental in helping us get some of the assays and interpretation for that model up and running,” said Dougherty. And for Gabel’s mouse models of TBRS, Dougherty’s group helped evaluate behavior.

We are so proud of Harrison’s achievements. He is a wonderful leader and a model mentor.

Linda Richards, PhD

By initiating collaborations within Washington University and with groups at other institutions, Harrison has established his lab as a global hub of research on TBRS. His leadership in the field has been recognized by his appointment to the Scientific Advisory Committee of the TBRS Community, the patient-led organization supporting research on this rare disorder. Harrison’s lab is continuing to investigate the etiology of Tatton Brown Rahman Syndrome and has contributed fundamental insights into the molecular and neurological consequences of DNMT3A mutations.

Gabel has made volunteering and outreach a defining feature of his lab. He frequently engages with patient groups to inform them about research and he serves on committees to enhance training opportunities for students from underrepresented backgrounds in neuroscience. His lab members follow suit and everyone volunteers their time or skills or some way. Last year, Gabel’s former graduate student Sabin Nettles, PhD, received the Society for Neuroscience’s Next Generation Award for her outstanding contributions to the Brain Discovery initiative, which brings neuroscience to classrooms in St. Louis.

“We are so proud of Harrison’s achievements. He is a wonderful leader and a model mentor with a highly engaging style,” said Richards. “He has set a high standard for himself and his laboratory members to provide an inclusive and supportive scientific environment that has enabled the team to be highly productive.”

Read more about the Gabel Lab

Sabin Nettles receives SfN Next Generation Award

Nettles has led outreach efforts to bring neuroscience into St. Louis classrooms, all while making inroads into the biology of Rett Syndrome for her graduate research in Harrison Gabel’s lab.

Serendipity unites physicians, researchers, families to fight rare genetic disease in kids

Groundbreaking cancer research helps shed light on recently identified syndrome

Collaborative team investigates protein that underlies CHARGE syndrome

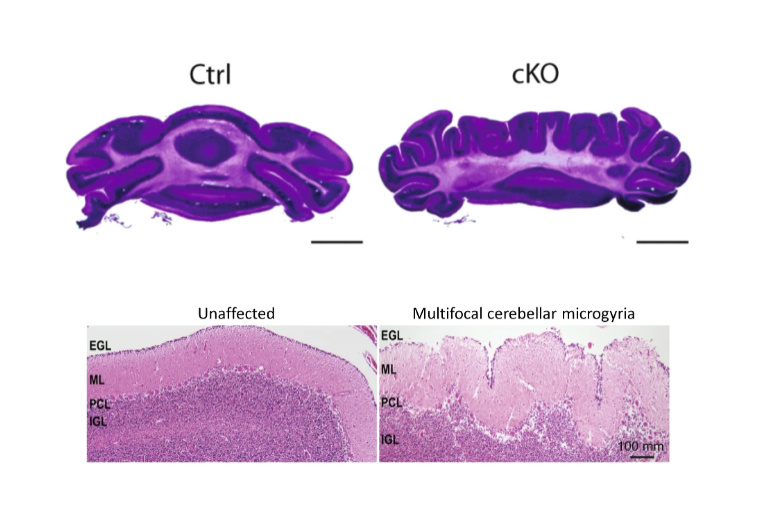

The researchers find that loss of the CHD7 protein in mice lead to changes in gene regulation and abnormal brain folds, indicating possible mechanisms for the rare neurodevelopmental disorder.