When Paul Bridgman was in high school in the 1960s, he attended one of his father’s lectures at the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine. “He was such a great lecturer—so dynamic,” Bridgman said. Charles Bridgman, who was a founding faculty member of the medical school, had been trained in medical illustration. During his lecture he drew anatomical structures on the chalkboard with captivating detail. When class ended, the students gave him a standing ovation. “I told myself I could never do what he did.” Nevertheless, the younger Bridgman pursued a career in academia, following in his father’s footsteps of scientific research and anatomy instruction—and becoming arguably as celebrated as his father.

For nearly 40 years Bridgman has been a professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine. As a neuroscientist he has made major discoveries on growth cone motility and as an educator he developed innovative teaching methods and instructional materials that have been widely adopted in histology courses. “He has this advantage of being super visual,” a talent pervasive among the Bridgman family, said Vance Lemmon, PhD, the Walter G. Ross Distinguished Chair in Developmental Neuroscience at the University of Miami and a longtime friend of Bridgman. “It’s especially useful in communicating the essentials of anatomy—it’s all about relationships in three dimensions.”

At the end of this month, Bridgman is retiring. Among the framed journal covers and boxes of CDs of digitized histology slides, he takes with him the highest honors given to educators at Washington University, including the Lifetime Achievement Award. “Paul is a very good example of a modest, effective and brilliant teacher,” said Krikor Dikranian, MD, PhD, Professor of Anatomy in Neuroscience. With Dikranian, Bridgman authored a book in 2015, the Guide to Medical Histology, which was published on iTunes. In retirement, Bridgman will turn his attention to writing a book on another topic of his expertise, an industry that originated in his parents’ garage.

The surfers of Starlight Drive

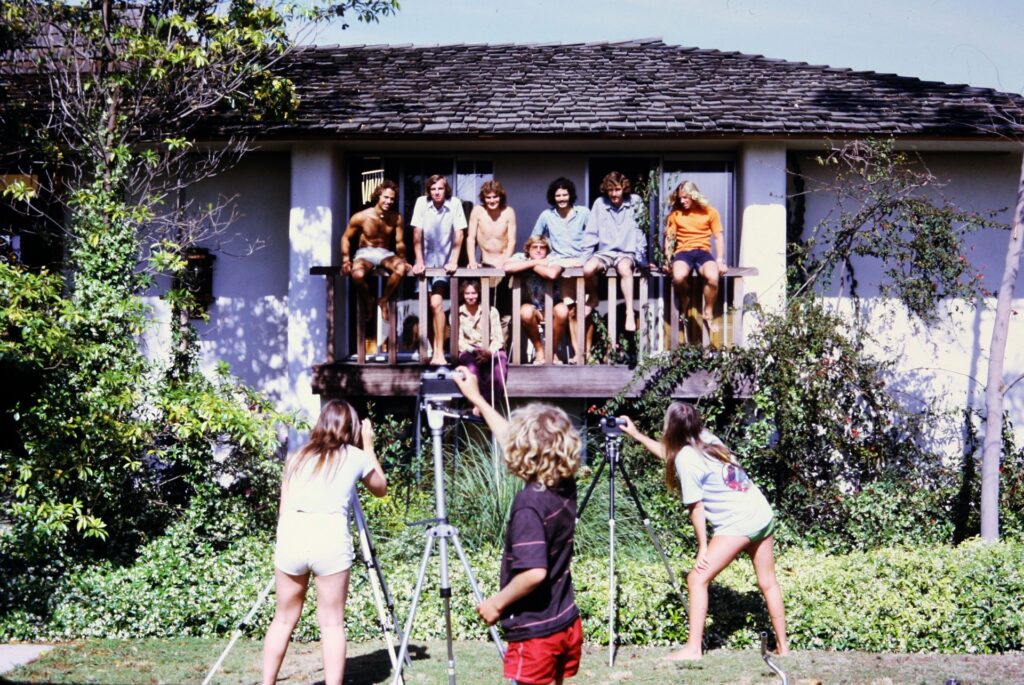

In his junior year of college at the University of California, San Diego, Lemmon found himself in need of a new place to live. He and his roommate went to the housing office to search the message board for open rooms and found themselves in disbelief at one of the listings. “We couldn’t believe the address!” he recalled. Starlight Drive—as majestic as it sounds—sits on the cliffs of La Jolla, dotted with massive houses that look out on the surf on one side and a canyon on the other. The home was owned by Paul Bridgman’s parents, Charles and Amy, who left the property to their children to rent out after Charles took a position at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

Lemmon moved in and found himself in a den of surfers. Brothers Paul and Dan Bridgman were UCSD undergrads, talented surfers, and among the first shapers to make surfboards in La Jolla. They had converted the Starlight home’s garage into a shaping studio for crafting boards, which attracted the likes of Rusty Preisendorfer, who started Rusty Surfboards and came to be a doyen of the industry.

Paul and Dan made boards under the Atlantis label and sold them directly to surfers or at Mitch’s Surf Shop in town. They were also well-respected athletes, known for surfing Black’s Beach in front of campus, where the nice left break of the surf suited their goofy-footed stance (right foot in front). “Professional surfers would stop to watch them,” said Lemmon. “Only once the surf got too big for me would they go out.”

Although Paul Bridgman would continue to surf for decades, his career took him far from the coast. Lemmon headed to Emory University for graduate school (and ended up living in Dr. Bridgman’s home there), while Bridgman received his PhD training at Purdue University. Bridgman then joined Tom Reese’s lab at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, first as a postdoc and shortly after as a staff fellow. In 1984, Bridgman joined WashU. Initially he studied acetylcholine receptors, but pivoted to investigating growth cones when he adopted an approach developed by colleagues Dick Bunge, MD, and Mary Bartlett Bunge, PhD, both professors in the Department. They cultured neurons from rodents, which allowed Bridgman to investigate the ultrastructure of the cell.

Neuroscientist and mentor

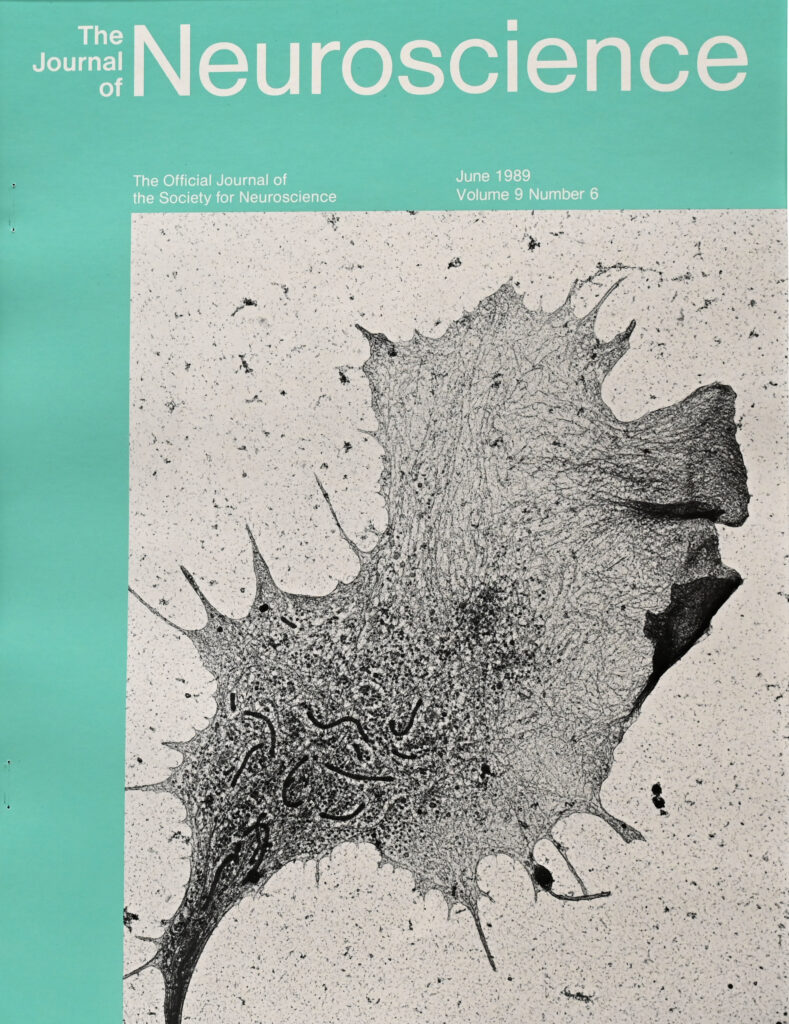

Bridgman and Mary Bunge teamed up to obtain a new electron microscope for the Department. Bridgman zeroed in on the organization of the cytoskeleton at the growth cone, making precise anatomical descriptions and defining different domains of the growth cone. Among his most influential papers was a 1992 study in the Journal of Cell Biology describing two distinct subpopulations of the cytoskeleton in the growth cone, indicative of different functions. This work attracted William Rochlin, PhD, to do a postdoc in the Bridgman lab. “He was definitely a star not only in electron microscopy but time-lapse imaging of growth cones,” said Rochlin, who is now an Associate Professor at Loyola University Chicago.

He is an amazing scientist and I owe my career to his mentorship.

Indra Chandrasekar, PhD

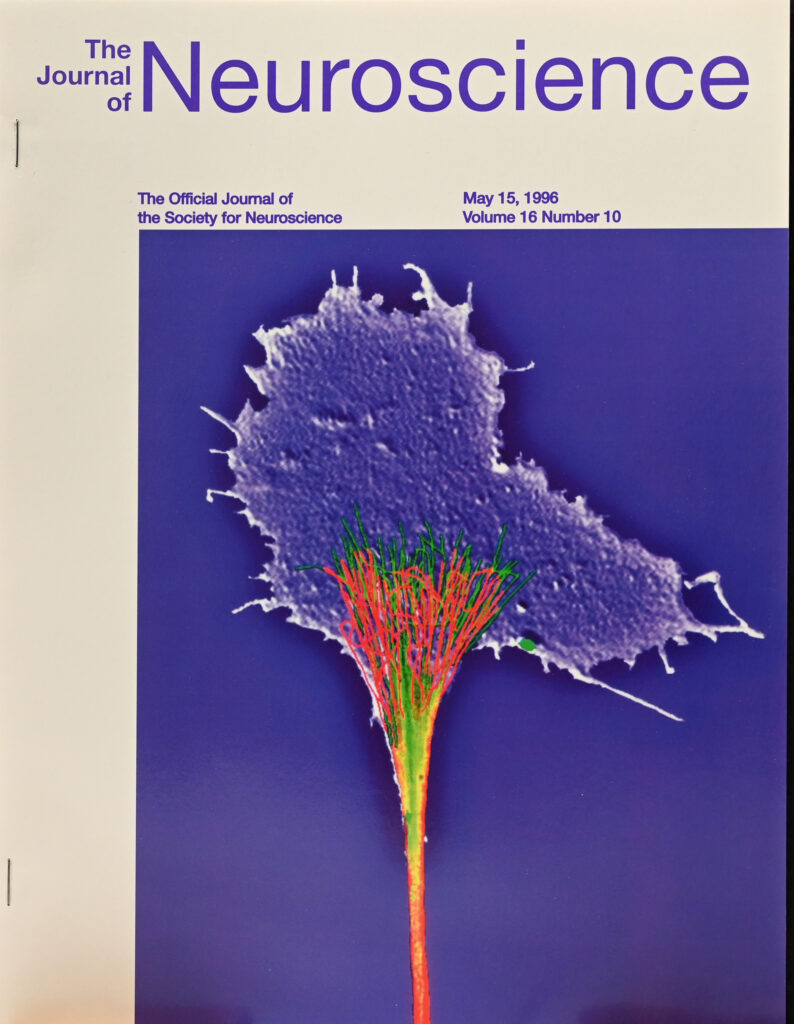

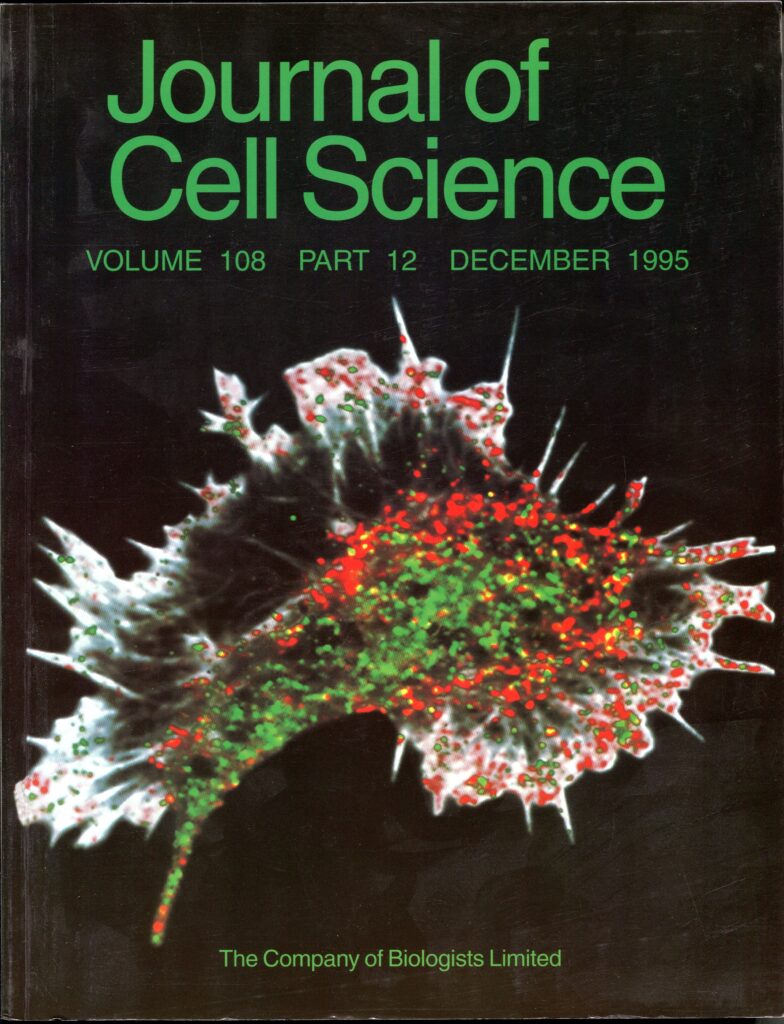

Because of Bridgman’s cell culture work, the lab could perturb various proteins to determine their function in neuron behavior. Rochlin focused on myosins, actin and microtubules. Their 1995 paper in the Journal of Cell Science mapped the localization of myosin isoforms within the growth cone and identified a potential role for myosin heavy chain B in creating the tension necessary to direct growth of neurites. Their stunning image of a growth cone graced the cover of that issue. “This is a lab where you were celebrating the beauty of the system as well as trying to understand how it works at the molecular level,” said Rochlin.

Rochlin said that the appreciation for aesthetics—in addition to the careful microscopy work that went into making these images—has stuck with him throughout his career. As a mentor, Bridgman’s calm demeanor and ability to foster independence while providing support “was an important advantage of working in his lab.”

Indra Chandrasekar, PhD, an Associate Scientist at Sanford Research, found this to be true when she joined the Bridgman Lab as a postdoc and launched a project on vesicle recycling at the synapse. Her project discovered a new function for myosin II: determining the strength of synaptic transmission by ushering released vesicles for endocytosis. Chandrasekar said the result was surprising given that myosin had been studied for 30 years without anyone finding this role. “Dr. Bridgman doubted the experiments initially until we could repeat it multiple times,” she said. Bridgman would join her in conducting experiments. His commitment to benchwork was inspired by Dale Purvis, MD, a professor at WashU for three decades who was in the Department of Neuroscience when Bridgman started. “I tried to emulate him because working at the bench (or microscope) for me is the most satisfying part of science,” said Bridgman. “As a result, during my career, I published or was associated with 15 research papers either as the sole author or in collaborations with other labs.”

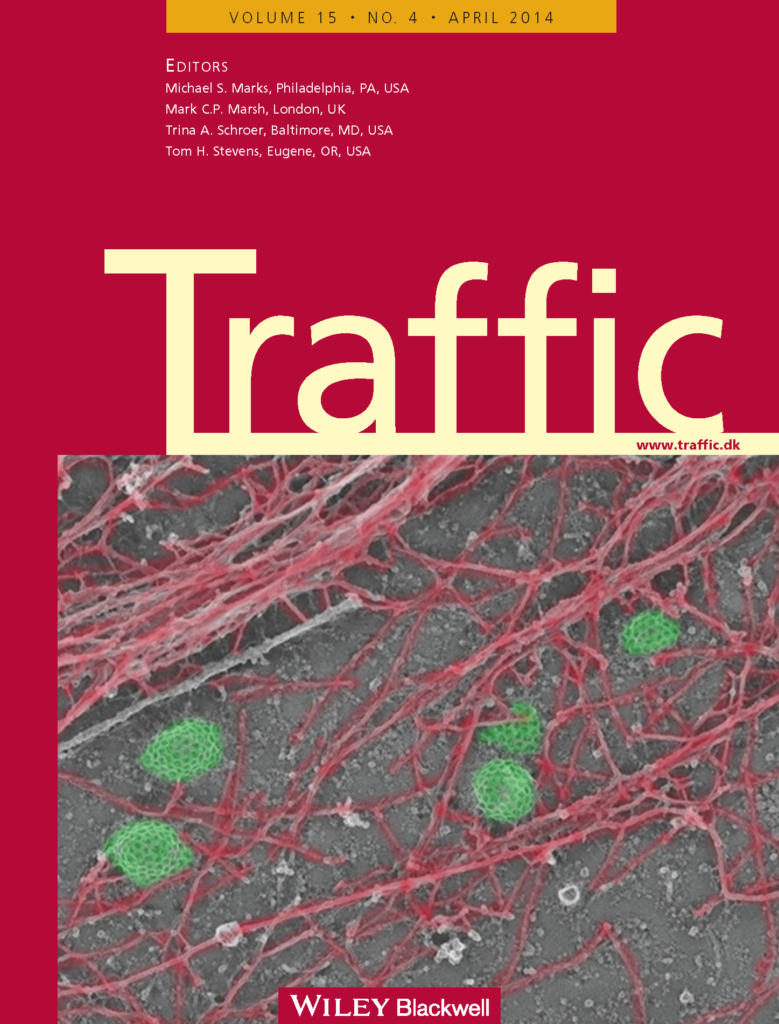

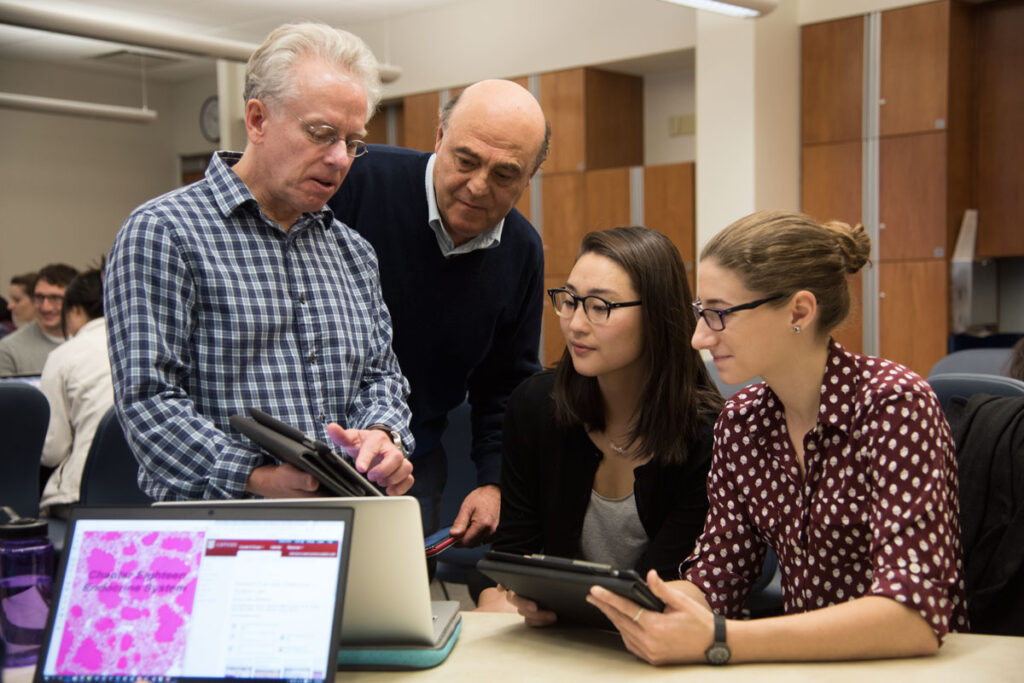

Chandrasekar and Bridgman published their findings in the Journal of Neuroscience in 2013 and in Traffic in 2014, the latter issue bearing an image from their work on the cover. Chandrasekar said she has continued this line of research in her own lab, examining the role of myosin in fine tuning membrane dynamics of kidney cells. “I wouldn’t have this career without the finding I had in the Bridgman Lab and pursuing that has worked out really well so far,” she said. “He is an amazing scientist and I owe my career to his mentorship.”

Revered educator

Throughout his decades as a principal investigator, Bridgman taught graduate and medical courses, most notably, the histology course for medical students. He was the course director from 1999 to 2020 and developed innovative approaches to teaching. He digitized the Department’s histology slide collection and developed a website, Slide-Atlas.org, to make these images accessible for teaching histology. “What he did on top was these histological images were annotated, so you could zoom to a certain feature and it will tell you the name of the cell and other information,” said Dikranian. He and Bridgman collaborated on a popular iBook, the Guide to Medical Histology, published in 2015, that featured the online atlas. “It was a pleasure to work with him,” said Dikranian. “We were a good team!” Dikranian co-taught histology with Bridgman. He said Bridgman was a great course director and presented the right balance of conceptual, basic science and clinical material.

Over the years, Bridgman won numerous awards for his teaching, including the Course Master of the Year Award, the Samuel Goldstein Leadership Award in Medical Education, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Academy of Educators.

All in all, Bridgman epitomizes the well-rounded scientist, tirelessly revealing both the mechanics and beauty associated with directed cell motility, designing tools that advanced the frontiers of neuroscience research and education, and fostering deeper appreciation of nature in his lab trainees, his classroom students, and colleagues.

William Rochlin, PhD

He’s also been an invaluable member of the community at WashU. He served in leadership positions on the Executive Committee of the Faculty Council, successfully advocating for new retirement benefits for faculty and pushing for change in the medical curriculum. As the School of Medicine transitioned to the Gateway Curriculum in 2020, Bridgman served on planning committees and as an instructor.

Bridgman’s retirement, which commences June 30, doesn’t mark the end of his career. He still has two scientific papers in progress and is going to turn his attention to writing his book on his surfing career.

“All in all, Bridgman epitomizes the well-rounded scientist,” said Rochlin, “tirelessly revealing both the mechanics and beauty associated with directed cell motility, designing tools that advanced the frontiers of neuroscience research and education, and fostering deeper appreciation of nature in his lab trainees, his classroom students, and colleagues.”