As a kid growing up on Staten Island, Matt Levendosky “always had a thing for fish,” he says, though not for the obvious reason of being surrounded by water. His dad was an aquarist at the Staten Island Zoo, and Levendosky would tag along at work to watch the animals swim in the tanks. “I always used to say, if I could find a job where I could stare at fish, I’d be happy,” he says.

Fast forward two decades, and Levendosky got just what he wanted. As a technician in the lab of Geoffrey Goodhill, PhD, Professor of Developmental Biology and Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine, Levendosky manages the zebrafish colony for the Goodhill lab—cleaning tanks, breeding animals, genotyping individuals, and, of course, watching them swim. The Goodhill lab studies neural computation underlying behavior, so observing the animals is part of the job.

The work of a lab tech is “extremely important,” says Goodhill. “They play a critical role in keeping everything running, and it would be very hard to function without them. When I first moved to Washington University, Matt was the first person I hired.”

Last week was the 2022 International Laboratory Animal Technician Week, organized by the American Association of Laboratory Animal Science. While caring for animals is a core responsibility of research technicians in labs that study them, it’s one piece of a complex job that spans all aspects of keeping a lab running smoothly.

“They integrate lab needs, ensure compliance, implement PI-driven guidance, onboard new lab members, coordinate animal needs, contribute to experiments, and act as the ‘face of the lab’ and point of contact for some outside partners,” says Assistant Professor of Neuroscience Thomas Papouin, PhD. “They embody the lab’s expertise and practical know-how, and they know all the ropes. So they are an essential counterweight to the inevitable transient nature of students and postdocs.”

Interested in a laboratory technician position in the Department of Neuroscience? See our open positions»

An evolving career

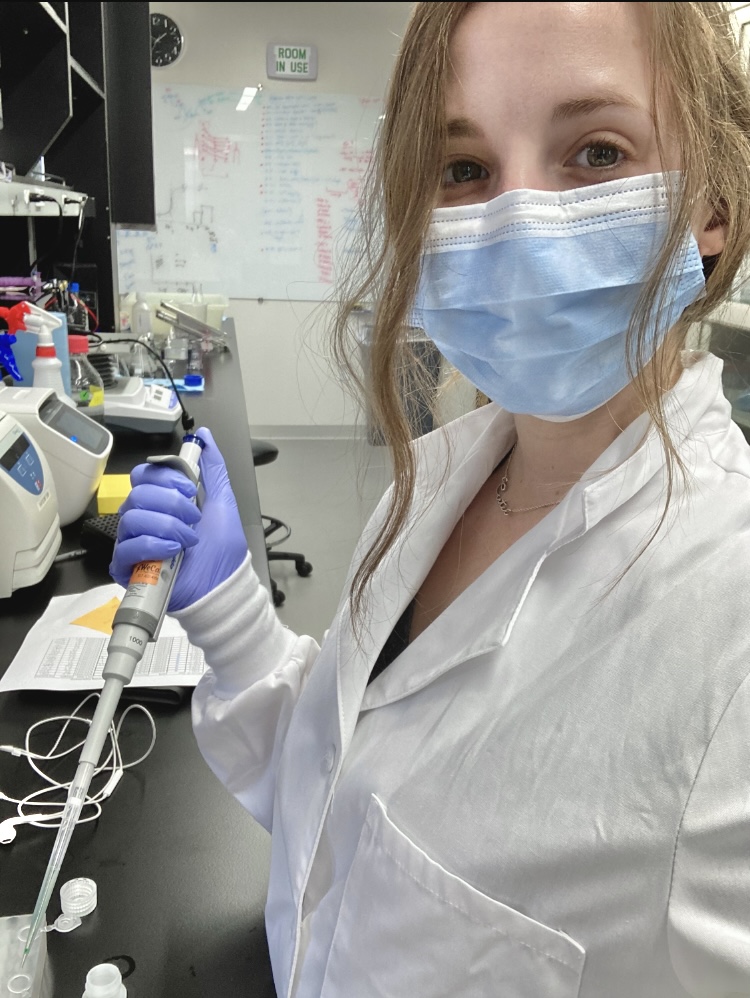

Sarah Mitchell, a research technician in the Papouin Lab, joined WashU after completing her master’s in behavioral neuroscience at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. There she studied the effects of a plant-based compound on chronically stressed rats to see if it might have a therapeutic benefit. As she was wrapping up her degree, she saw a talk by Dr. Papouin, and was drawn to the research by its combination of behavioral, molecular and genetic components. Mitchell was interested in joining the group, but didn’t have the molecular biology skills she thought were a prerequisite.

Being a tech can be a way of gaining experience in a lab for a couple of years before applying to grad school, it can be a much longer-term position supporting an individual lab, or it can lead on to positions with broader levels of responsibility such as a running a particular core facility.

Geoffrey Goodhill, PhD

“I felt the job was out of my league,” she says. “When I started in the lab, I had used a pipette about five times. I was starting from the bottom, but I had a great PI who was willing to help me learn. As long as some of your skills align with the job, then you can learn the others.”

That ability to learn and adapt is a critical skill to be a successful technician, says Papouin. No research tech can come in knowing every technique and process in a given laboratory—afterall, labs’ methods and approaches change over time, and the exact duties of a lab tech will too. Mitchell says that learning new techniques has been one of her favorite parts of her job.

For Heide Schoknecht, a research lab supervisor for Camillo Padoa-Schioppa, PhD, Professor of Neuroscience, that approach to learning on the job led to her earning a second bachelor’s degree. For her first undergraduate degree, she had studied communications, German and biology at the Missouri State University. Schoknecht came to WashU as a research technician in 2008, working with nonhuman primates. It was a new experience, and “I really wanted to prepare myself as much as possible for working with the animals,” she says. “I think continuing education and staying up-to-date on current research is really important.”

Schoknecht took advantage of WashU’s tuition benefit for employees, and registered for courses on primatology and related studies, eventually completing a second bachelor’s degree in anthropology. She says she’s applied the knowledge from her degree to caring for the animals, developing enrichment materials, and generating high-quality observational data.

“Heide is unusually capable,” says Padoa-Schioppa, both in her technical skills in working with animals, but also in managing research operations. “She writes protocols, trains new lab managers, makes purchases, and takes care of the lab in a physical sense,” he says.

Schoknecht is also a team leader among the technicians and has worked with entities that oversee animal research to be sure the lab is in not only in compliance but using the most state-of-the-art approaches to caring for lab animals. She served on the committee to update the training modules for nonhuman primate (NHP) staff at WashU. “Her expertise and contributions will help the entire NHP research community – not just the lab she works in,” says Meredith Moore, PhD, Director of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at WashU.

When the Padoa-Schioppa group, which is investigating the fundamental mechanisms of decision-making, expanded to study mice, Schoknecht took on the responsibility of managing the rodents. She says one of her favorite aspects of being a research technician is that it’s a constantly evolving role. “It never gets boring,” she says.

For Matt Levendosky, the opportunity to learn new skills as a technician is appealing for his career development, as he is considered pursuing a PhD. He received a master’s degree from Georgia Southern University, where he studied anesthesia in sharks and rays, before coming to the Goodhill lab. “Being a tech can be a way of gaining experience in a lab for a couple of years before applying to grad school, it can be a much longer-term position supporting an individual lab, or it can lead on to positions with broader levels of responsibility such as a running a particular core facility,” says Goodhill.

With such diversity in the field, research tech positions can accommodate just about any interest or goal, with the common thread of enjoying looking after the laboratory animals. “For animal lab techs,” says Mitchell, “it’s important they care for animals and have respect for them.”

Research positions open in the Department of Neuroscience

Optical Engineer/Imaging Scientist (Postdoctoral Research Associate/Staff Scientist/Senior Scientist)

Neuroscience

The successful applicant will design, build, and characterize innovative optical instruments for fluorescence microscopy applications in Dr. Yao Chen’s laboratory.

Postdoctoral Research Associate / Senior Scientist / Staff Scientist / Sr. Research Technician (Cavalli Lab)

Neuroscience

The laboratory of Dr. Valeria Cavalli is seeking passionate scientists to join their team and contribute to our NIH-funded research projects on the multicellular mechanisms promoting axon regeneration in mouse and human models.

Staff Scientist (Oviedo Lab)

Neuroscience

The Oviedo lab is conducting groundbreaking research on the development of the brain’s communication centers and how they are impacted by neuropsychiatric disorders.