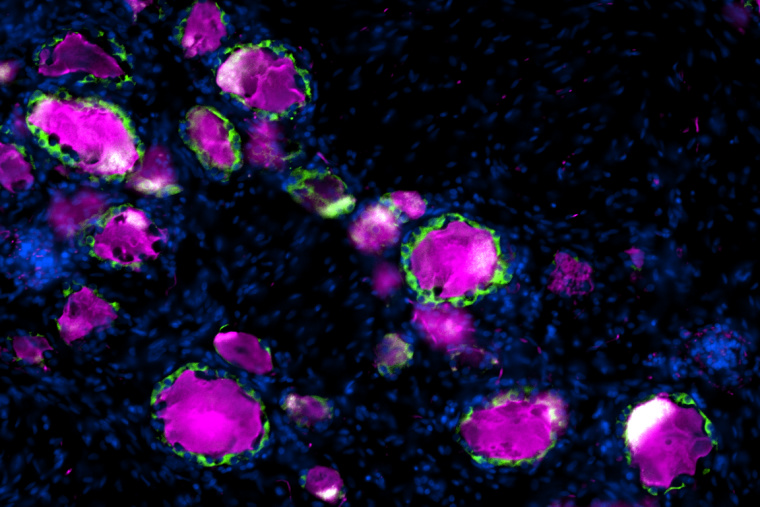

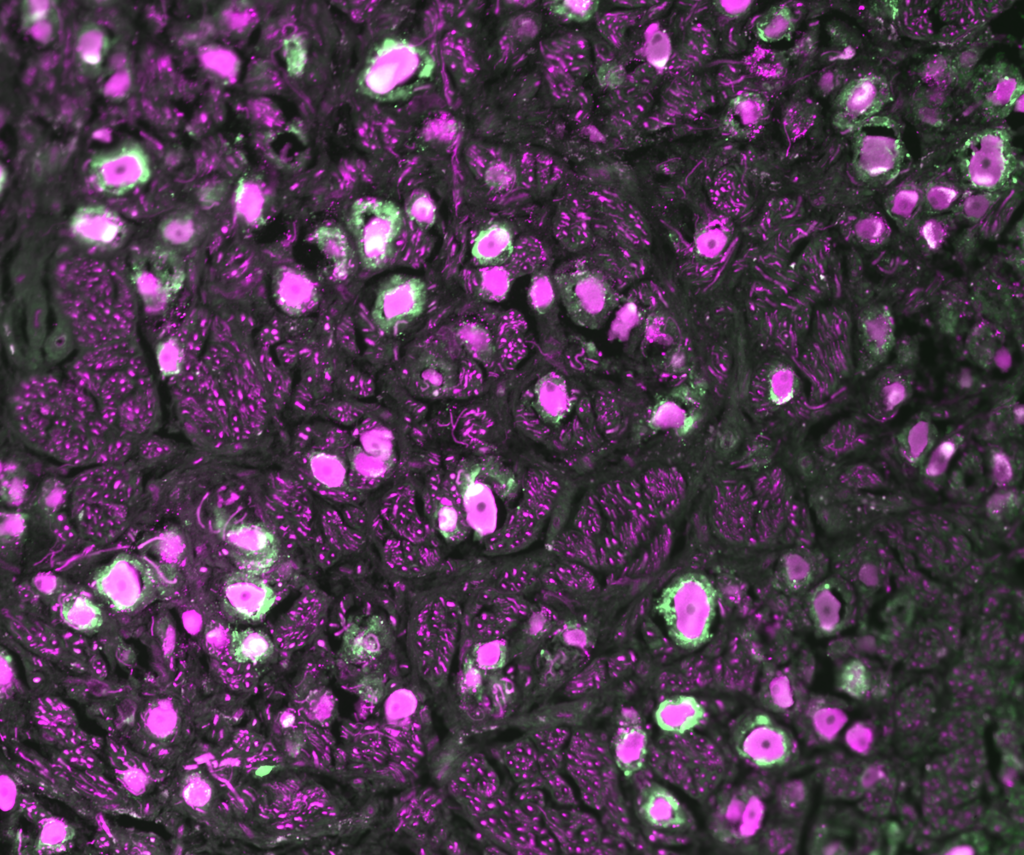

En route from the periphery to the central nervous system reside dorsal root ganglia, clusters of neuronal cell bodies near the spinal cord that relay sensory information to the brain. Wrapped around each DRG neuron is a satellite glial cell, a partner in sensory transmission that has been implicated in chronic pain and nerve repair. Most of the studies to date on SGCs have been in rodents without a clear understanding of how well they represent human SGCs. In a study published in Pain, researchers from the Departments of Neuroscience and Anesthesiology at Washington University School of Medicine compared mice, rat and human SGCs, finding key similarities that confirm rodents’ use as a model to study these intriguing cells.

“We were excited to see that the pathway we identified in mouse SGC, which we previously showed contributes to promote nerve repair, is conserved in human SGC,” said coauthor Valeria Cavalli, PhD, the Robert E. and Louise F. Dunn Professor of Biomedical Research in the Department of Neuroscience. “We also observed similarities in ion channel and receptor composition between human and rodent SGCs, which suggests that SGC functional roles are conserved across species.”

The study of human DRGs was made possible in 2016 by Rob Gereau, PhD, the Dr. Seymour & Rose T. Brown Professor and vice chair for research in the Department of Anesthesiology, and colleagues, who developed a technique to obtain the cells from tissue donors post-mortem. This advance enabled the current study, of which Gereau is a coauthor, to compare the gene expression profiles of individual SGCs from rat, mouse and human.

The authors found key similarities among the SGCs from different species, in particular, enrichment of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARα) signaling, a pathway involved in fatty acid metabolism. This is important for potential therapeutic development, as Cavalli’s group previously reported that stimulating this pathway using an FDA-approved drug, the PPARα agonist fenofibrate, can increase axon regeneration following dorsal root injury in mice. “The observation that PPAR signaling is similarly enriched in human and rodent SGC opens the potential for pharmacological repurposing of fenofibrate and that manipulation of SGC could lead to avenues to promote functional recovery after mechanical or chemical nervous system injuries,” said Oshri Avraham, PhD, a staff scientist in the Cavalli Lab and the lead author of both studies.

The team also observed notable differences between species. For instance, Cavalli pointed out, studies on pain in rodents have focused on a potassium channel called Kir4.1 that her group found is only weekly expressed in humans—SGCs from donors instead express Kir3.1. Documenting these differences is useful for translational studies to ensure that models appropriately recapitulate the biology of human patients. “The unique insights provided by the study of human dorsal root ganglia are the clear demonstration that the critical cell types and signaling pathways their group identified in mouse models are present in humans, and as such the potential therapy that they showed to be effective in mice holds great promise for similar efficacy in people,” said Gereau.

Interested in this research? The Cavalli Lab has opportunities to join their team.