Weston et al., Nature Communications, 2021

For individuals with rare diseases, the journey to a diagnosis can be a long and frustrating experience, sometimes ending with no answers. Such was the case with a few patients of Marwan Shinawi, MD, a Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Genetics and Genomic Medicine at Washington University School of Medicine. They each were found to have variants in the UBE3A gene, which underlies Angelman syndrome, but none of them had the classic symptoms of the disorder. Angelman syndrome ordinarily causes intellectual disability, epilepsy, small head size, sleeping problems, and a happy disposition.

To get answers, Shinawi turned to Jason Yi, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Neuroscience. Yi and his colleagues had been working on developing a fast approach for analyzing the functional consequences of so-called variants of unknown significance—genetic mutations whose relationship to a disorder isn’t clear. In a recent study in Nature Communications, they gathered dozens of UBE3A variants from a clinical database and ran them through their newly developed assay to determine how the mutations affect the activity of the protein. Many of the mutations caused a loss of protein function, already known to occur in Angelman syndrome, but a number of variants, including those of Dr. Shinawi’s patients, led to a gain of function of UBE3A.

Shinawi says his patients likely have a UBE3A-related disorder distinct from Angelman syndrome. “Dr. Yi’s group successfully developed a large-scale and rapid functional assay to determine the effect of UBE3A variants on its function,” says Shinawi. “These results helped me as a clinician to determine that the results are in fact the diagnostic answer for their underlying genetic condition.”

A new assay for variants of unknown significance

Yi had initially linked a gain-of-function variant in UBE3A to a child with autism during his postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. But, being a single example, it was unclear if this represented a general relationship between gain-of-function variants in UBE3A and autism. There was certainly a need to find out; in genetic databases, doctors have deposited hundreds of UBE3A mutations. “Most of them, we don’t know what they do,” says Yi.

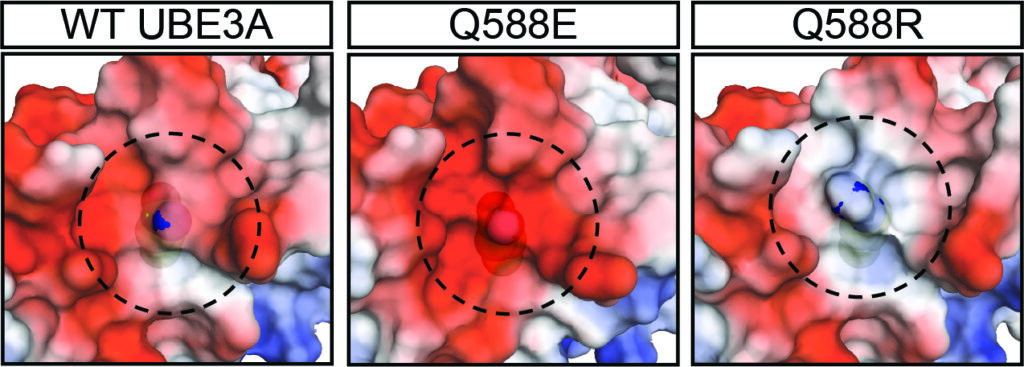

To use traditional methods of measuring the activity of UBE3A is a laborious process, so in his latest study Yi adapted an assay using a luciferase reporter system that allowed him to efficiently read out UBE3A function in cells. His assay paired luciferase, a bioluminescent protein, with a signaling component downstream of UBE3A activation, so that the greater the UBE3A activity, the stronger the luciferase glow. He says it was exciting when his team, co-led by graduate student Kellan Weston and research technician Xiaoyi Renee Gao, now a medical student at St. Louis University, identified the first gain-of-function variant using the assay. This suggested Yi’s discovery from years past wasn’t the only instance—and then came another, and another, until they had amassed 18 gain-of-function mutations.

Further experimentation revealed that there doesn’t appear to be extra UBE3A, but rather the enzyme is more active in its housekeeping role of degrading proteins in the cell. Yi says he’s interested in exploring why these variants cause increased UBE3A activity and how they affect brain function. His work could also help clarify some of the molecular underpinnings of another rare genetic disorder called Dup15q syndrome. In those individuals, a region of chromosome 15 that includes UBE3A is duplicated, leading to autism, low muscle tone, cognitive delays, and other conditions. “The questions is, are those the result of UBE3A,” Yi says, “or is UBE3A just carried along?”

Weston notes that solving questions about the underlying molecular mechanisms of syndromes intends to not only end the diagnostic journey for patients, but to help families on the next phase too—what to expect after a diagnosis of a rare disease. “We are still in the dark ages of prediction of outcomes for rare diseases,” she says.

Shinawi says one of the biggest lessons learned from the study is that clinicians shouldn’t ignore variants of unknown significance in their patients because there can be alternative mechanisms driving disease. In the case of UBE3A, the hazards of excess activity of the protein Yi, Weston and their colleagues illuminated are important to consider in the development of therapeutics for Angelman syndrome that seek to ramp up UBE3A activity. “The study illustrates the significance of collaboration between the scientific community and clinicians,” Shinawi says.