The body’s ability to repair itself after nerve damage is inconsistent—some injuries heal while others cause lifelong disability and pain. Adjacent to the spinal cord, in a tissue called dorsal root ganglia, are cells that experience both. So-called dorsal root ganglia neurons, which are responsible for communicating sensory information, have two branches, one axon that travels along peripheral nerves and can fix itself after an injury and another axon that dives into the spinal cord and does not heal from damage.

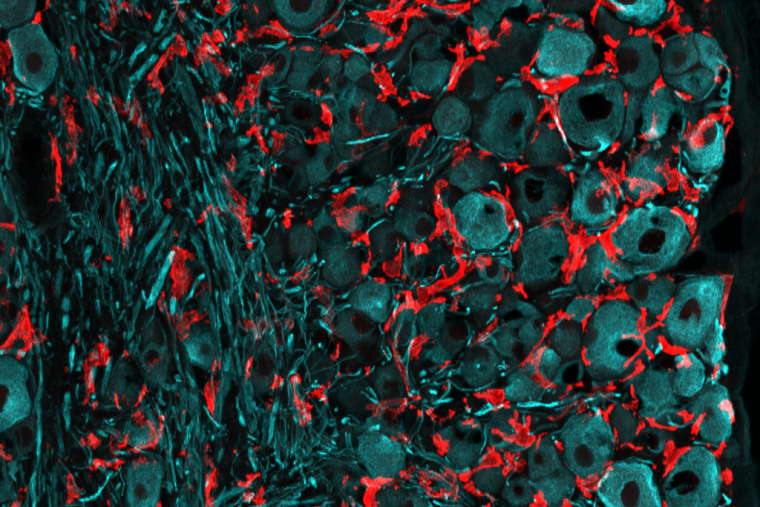

In an effort to understand what makes it possible for the peripheral branch of the dorsal root ganglia neurons to repair damage, the laboratory of Valeria Cavalli, PhD, investigated the role of immune cells called macrophages that accumulate after injury. These cells have been implicated previously in both nerve repair and chronic pain. In a study published in PNAS on February 10, 2023, the researchers describe various types of macrophages present after nerve damage, including resident cells that proliferate and work with surrounding satellite glia cells and contribute to nerve repair.

“These results might help untangle the immune mechanisms regulating nerve repair versus those that promote chronic pain,” said Cavalli, the Robert E. and Louise F. Dunn Professor of Biomedical Research in the Department of Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine.

Cavalli’s group studied mice with peripheral nerve injuries to determine the source of macrophages that arrive to the scene in dorsal root ganglion, dubbed DRGMacs. The largest population of DRGMacs originated from resident macrophages that proliferated in response to injury. In contrast, in peripheral nerve, damage typically recruits macrophages from the bone marrow. These resident responder cells in the dorsal root ganglia proved helpful to nerve repair. There was less nerve regrowth when the researchers impaired the ability of resident DRGMacs to expand in number, compared to in mice with DRGMacs that could self-renew. They also found that self-renewing DRGMacs stimulated the growth of dorsal root ganglion axons in a dish.

To dig down into how locally populated DRGMacs promote regeneration, the team examined communication between the macrophages and surrounding cells, in particular, satellite glial cells. The Cavalli Lab previously showed that satellite glial cells, which surround the cell bodies of dorsal root ganglia neurons, are important for nerve repair. In this latest study, they observed cross-talk between cells via various pathways, but one form of communication stood out: DRGMacs sent satellite glial cells and endothelial cells signals through the prosaposin pathway, which is known for its neuroprotective, glioprotective and analgesic properties. The finding provides a lead for exploring new treatment options.

“Future studies are needed to determine how the distinct subpopulation of DRGMacs evolve in time, which may inform future therapeutic approaches to treat nerve injury to promote recovery without pain,” the authors write in their paper. The team also plans to explore the role of the other populations of DRGMacs they identified in this study.