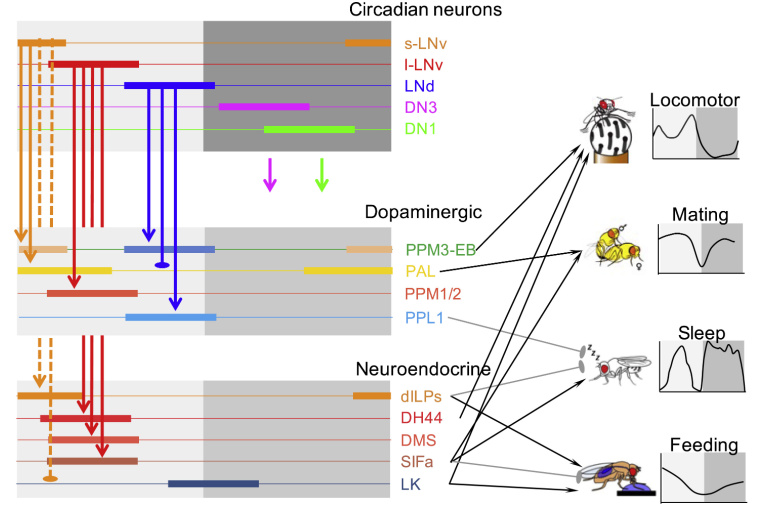

Within the fruit fly brain’s 100,000 neurons is an organized set of circadian pacemakers—150 cells that possess an intrinsic 24 hour clock that is highly sensitive to daily light and dark cycles. They’re divided into roughly five groups with the activity of each one aligned with a different portion of the day, either morning, mid-day, evening, or one of two at night. In a recent study in Current Biology, the groups of Professor Paul Taghert and Professor Tim Holy in the Department of Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine collaborated to identify correlated rhythms in downstream, non-pacemaker neurons that transduce pacemakers’ signals into behavioral cycles. While this team had previously described downstream brain centers that relay the oscillations from the Morning and Evening pacemakers, this latest work cements the functional relevance of a distinct oscillator group, termed Mid-day pacemakers. That finding underscores the conclusion that this dedicated timing circuit is a polyphasic rhythm generator.

“We speculate that the daily activity patterns we did measure here in certain non-pacemaker subsets are indicative of similar biased activity patterns in many other brain cells and centers,” said Taghert. “In other words, the polyphasic activity patterns generated by the pacemaker network are broadly distributed and used across the brain” to orchestrate when a fly sleeps, eats, mates, or carries out other daily activities.

It’s been the goal of the Taghert Lab to track the neural circuits that turn pacemakers’ rhythms into routine behaviors. Like any animal, fruit flies are creatures of habit: in their case, they’re most busy in the mornings and evenings, mating and eating, and in between they sleep. The group’s prior work, led by former graduate student Xitong Liang, had shown that morning and evening pacemaker neurons direct activity in downstream neural centers that in turn promote locomotor activity.

Building upon these findings, the team measured the daily activities of two types of non-pacemaker cells in the brain, dopaminergic (DA) and neurosecretory (NS), which are known to regulate behaviors in Drosophila, to see if they also produced daily activity rhythms. Indeed, that’s what they found: many (though not all) clusters of DA or NS cells displayed daily rhythms and their correlated behaviors followed the activity phases of distinct groups of pacemakers. Extending their earlier findings, they observed that morning and evening behaviors lined up with the activity of Morning and Evening pacemakers along with the activity of distinct DA or NS cells.

For the first time, the team established these functional links for a separate set of circadian oscillators—Mid-day pacemakers. For instance, diverse neurosecretory cells in the pars intercerebralis (PI), thought to regulate sleep, locomotion and metabolism, peaked at mid-day, in time with Mid-day pacemaker neuron activity. Among PI cells are those that promote sleep and mating and suppress feeding, which is precisely what flies are up to at mid-day.

Delaying the Mid-day pacemakers’ phase of activity delayed that of the correlated followers, indicating that the rhythms of the dopaminergic and neurosecretory centers and their associated behaviors depend on the clock.

Taghert said one of the big questions remaining is how rhythmic signals are transmitted from pacemakers to their downstream partners. “The downstream neurons we have studied do not have strong clocks to drive endogenous activity,” he said. “So understanding how a pacemaker phase is delivered to, and then transduced by, a downstream non-pacemaker to create a multi-hour period of neuronal activity represents an important question.”