CHARGE syndrome is a congenital genetic disorder that affects 1 in 12,000 births and includes a wide range of neurodevelopmental defects affecting several tissues, including the brain’s cerebellum. Insufficient levels of CHD7, an epigenomic regulator that regulates chromatin, causes this disorder; yet how CHD7 controls the chromatin states in the developing brain and contributes to the pathogenesis of this rare disease remains incompletely understood.

A team of researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis report in Nature Communications that CHD7 protein regulates epigenomic activation of the enhancers of the genes associated with brain morphogenesis. Depletion of CHD7 in granule cells of the cerebellum in mice leads to aberrant brain folding, a pattern that was also found in a CHARGE syndrome patient. This study, co-first authored by former graduate students Naveen Reddy and Shahriyar Majidi and Lingchun Kong, a former postdoctoral fellow, sheds new light onto the understanding of CHARGE syndrome, especially in the cerebellum morphological abnormality.

This phenotype is impressive, something we have not seen before.

Azad Bonni, MD, PhD, Senior Vice President and Global Head of Neuroscience and Rare Diseases at Roche Pharma Research and Early Development

Chromatin remodeling is an important epigenetic regulatory mechanism for gene expression. CHD7 belongs to a family of chromatin remodeling enzymes, whose members, such as CHD4, have been implicated in neurodevelopmental disorders including intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders. With mutations in the gene that encodes CHD7 leading to CHARGE syndrome, “it becomes an interesting target to not only understand the basic molecular mechanism of chromatin regulation in brain development, but gain insight into the disease pathology,” says co-corresponding author Harrison Gabel, PhD, assistant professor of neuroscience.

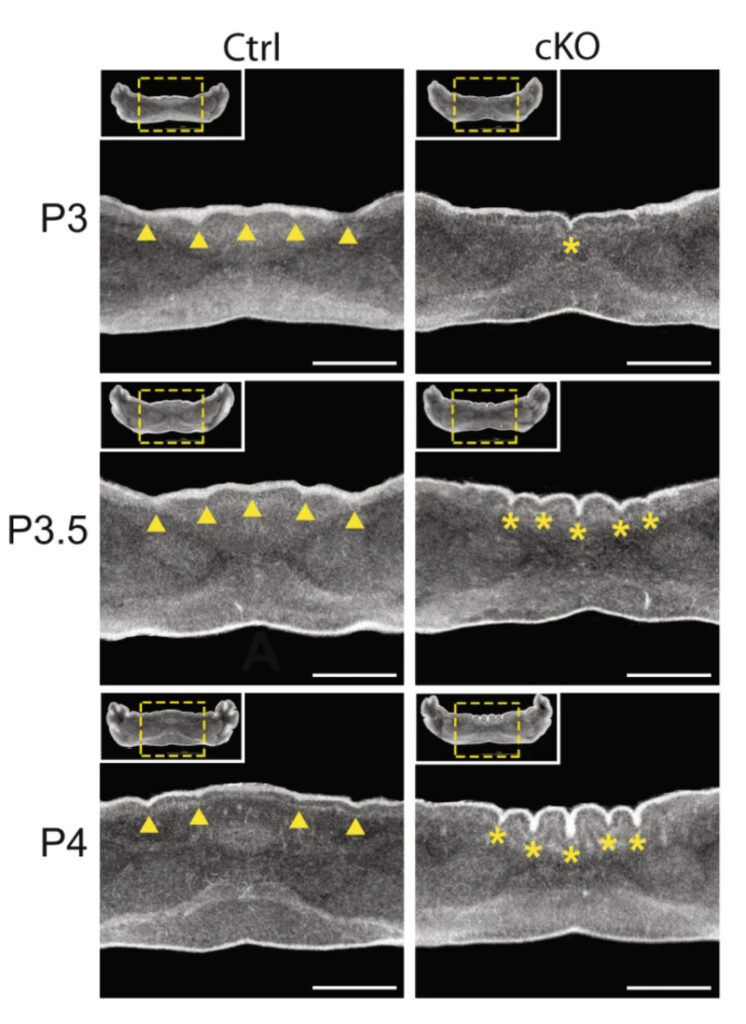

To answer basic questions surrounding CHD7’s function, the researchers knocked out the gene for CHD7 in the precursors of granule cells, the most abundant neuronal cell type in the cerebellum. Then, they used X-ray microscopy, a technique that can image a 3-D volume of a large sample in sub-micron resolution, to observe any morphological alterations in the brains of these mice. “X-ray microscopy is non-invasive and allows us to digitally slice through the whole brain to identify a specific brain folding pattern,” says collaborator James Fitzpatrick, the scientific director of the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging (WUCCI), who was among the first groups to apply this imaging technology in biological tissues. “Without creating tissue damage that usually occurs in conventional sectioning-based 3D reconstruction methods, it essentially allows us to do histology without doing histology.”

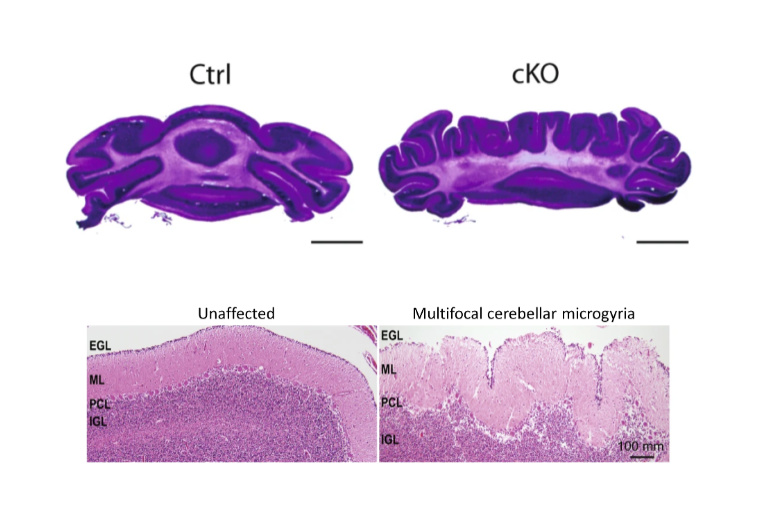

With this advanced imaging technique, the team observed cerebellar polymicrogyria – a misfolding of the cerebellum tissue. The loss of CHD7 “creates eight additional folds in a usually smooth region,” says Naveen Reddy, PhD, who conducted the work as a graduate student in the Department of Neuroscience and is now a scientist at Chroma Medicine. “It is always eight folds, very consistent, and is one hundred percent penetrant.”

Strikingly, Reddy and his colleagues also found a CHARGE syndrome patient with a similar brain folding abnormality, indicating that the mice are recapitulating some aspects of the disorder.

“This phenotype is impressive, something we have not seen before,” says co-corresponding author Azad Bonni, MD, PhD, Senior Vice President and Global Head of Neuroscience and Rare Diseases at Roche Pharma Research and Early Development, in whose laboratory the project was performed, while he was head of the Department of Neuroscience at WashU. “It suggests that epigenomic regulators orchestrate brain folding during development.”

CHD7’s genomic and cellular effects

Genome architecture analyses of the mice revealed that CHD7-dependent regulation of chromatin may underlie such morphological changes. Using next generation sequencing–based assays, the team found that CHD7 acts predominantly as an “activator” by promoting chromatin accessibility, active histone modifications and RNA polymerase recruitment at enhancers. “It’s a facilitator of gene expression, which doesn’t necessarily tell the cells which genes to turn on, but helps the cells to turn on the right genes at the right time and place,” says Gabel.

This figure shows a 24-hour time course from postnatal day 3 (P3) to day 4 (P4) as the abnormal cerebellum folds emerge in a mouse lacking CHD7 in granule precursor cells (right three panels) compared to a control mouse (left three panels).

N.C. Reddy et al.., Nature Communications, 12:5702, 2021

The team also found that deletion of CHD7 specifically in the granule cell precursors changes the axis of division in these cells from a normally anterior–posterior orientation to a preferentially mediolateral orientation, which helps to explain the brain folding deficit in cerebellum.

Collaborations from departments across the school of medicine allowed for such a broad investigation, from the molecular to the behavioral; the human brain sample, for example, was obtained from the Department of Pathology, while Guoyan Zhao, PhD, assistant professor of neuroscience, facilitated the analysis of data mapping the architecture of the DNA in the nucleus of cells in normal and CHD7 mutant cerebellum. “We are really appreciative to have such a collaborative effort from people at WashU,” says Gabel.

In the future, the team will look into the molecular mechanisms by which CHD7 manipulates the genome to further understand the cause of CHARGE syndrome. The researchers say they hope their pioneering observation in the human sample can provide the field with direction to look into a cerebellum folding anomaly in the disorder. “It will be interesting to see if there are additional cases to examine, and it is important to know if the epigenomic mechanisms uncovered in this study apply to human cells,” says Bonni.